This past weekend, Austrian drag queen

Conchita Wurst won the 2014 Eurovision song contest with the song,

“Rise Like a Phoenix.” Her

initial performance at Eurovision sparked some mean-spirited commentary, not

just because Conchita Wurst is the drag alter-ego of Tom Neuwirth (whose stage

name “Wurst” means, not so subtly, “sausage” in German), but notably because

Conchita performs in women’s clothes, with long hair, long eye lashes, plenty

of make up and a full beard.

Of course, as someone writing about beards, bearding, and

facial hair, I could not be more pleased by Wurst’s gender-bending performance

and the fact that in spite of/because of her appearance, Conchita won. The

importance of Eurovision as a song contest or a European unification event is

debatable, though its political commentary this year, given the tensions

surrounding the Russian presence in Ukraine and annexation of the Crimea, was

undeniable. Still, it’s a big event with millions of people watching, so it

gets significant exposure.

Front and center in these debates were the anti-gay laws recently

passed in Russia. One of Wurst’s most virulent detractors was Vitaly Milonov,

who was instrumental in writing the law against “homosexual propaganda” in

Russia, and who petitioned for removing Wurst from the competition, citing that

she was turning Eurovision into a

“hotbed of sodomy.”

Luckily, Conchita herself takes a more relaxed view of

the controversy. In response to a reporter who asked her reaction to the claims

she was a “pervert” should leave the content she said, “

I have very thick skin.

It never ceases to amaze me just how much fuss is made over a little facial

hair.”

|

| A "little" facial hair or a lot, it created a lot of fuss. |

A little facial hair, however, can mean oh so much, as I

have already discussed here. To recap, facial hair and beards especially have

been essential constructions of Western masculinity for hundreds of years.

According to Renaissance historian Will Fisher, “facial hair was… ideologically

central in the construction of masculinity.” To be male and adult in the

Renaissance, Fisher argues, is to be bearded. In the eighteenth century, the

beard becomes unfashionable—yet it is still made to matter.

The act of shaving became, in various places in Europe in

the eighteenth century, crucial to the construction of Western civilized masculinity. Modern categories

of race began to be theorized by eighteenth-century natural historians who linked

male heat and semen with the growth of facial hair, further associating beards

with mature, civilized masculinity.

|

A Russian Beard-tax token from the time of

Peter the Great, who wished to discourage the growth of beards,

which he deemed un-civilized. |

The case of

bearded women, then, was problematic, as they immediately put into question the

notion of gender categories and suggested a problem with the established

continuum of smooth and bearded faces. Jacques-Antoine Dulaure’s Pogonologia: or a Philosophical and

Historical Essay on Beards, was translated from the French and published in

England in 1786. The essay contains its own chapter of bearded women.

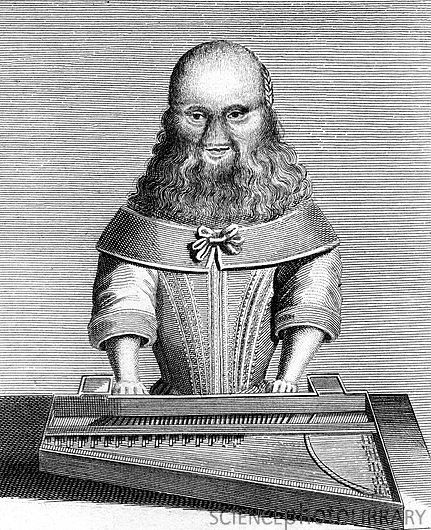

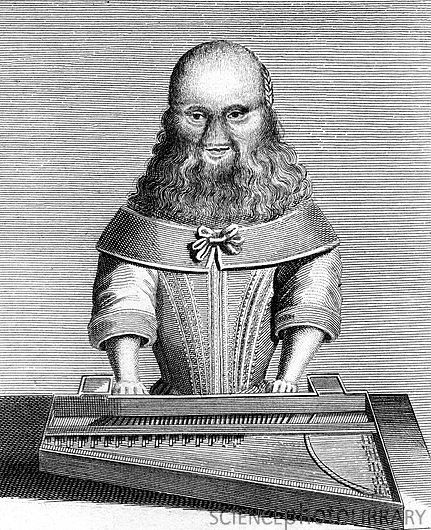

|

Portrait of Barbara Urselin,

17th-century German bearded lady playing a harpsichord. |

According to Dulaure, “a Woman with a beard on her chin

is one of those extraordinary deviations with which nature presents us every

day.” He cites various historical examples of bearded women who were quite

contented with their beards, including “a female dancer [in Venice who]

astonish[ed] the spectators, as much by her talents, as by her chin covered

with a black, bushy beard.” Surely this entertainer is the spiritual ancestor

of Conchita Wurst!

Another proud beard-sporting woman cited by Dulaure was

the “governess of the Netherlands… she had a very long, stiff beard, which she

prided herself on; and being persuaded that it contributed to give her an air

of majesty, she took great care not to lose a hair of it. This Margaret was a

very great woman.”

While these women are perhaps deviations from Nature,

Dulaure also notes that many ladies grow errant hairs on their faces and must

pluck them. Similarly, Sarah Scott’s A

Journey Through Every Stage of Life includes a cross-dressing character,

Leonora, who finds herself under scrutiny by older women for not being hairy

enough in her men’s attire.

Scott writes, “the Widows indeed, and some of the more

experienced Matrons, looked with a Mixture of Scorn upon her [Leonora], and the

antient [sic] Ladies especially, to whose Chins Age had given an Ornament that

even Leonora’s Manhood could not boast.”

Even Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders remarks that, when

considering cross-dressing as a disguise for stealing in, she is “a little too

smooth-faced for a man.” The notion, then, of women more generally having

whiskers is not unheard of in the texts of the time period.

In our own time and place, maintaining control over body

hair is

de rigueur. Even men refer to

“man-scaping” and rebel from the constraints of socially-expected grooming habits

during

“No-Shave November.” Women who refuse to properly control their body

hair are castigated or shamed. One has only to think of Julia Roberts being

attacked in the media for showing a hairy armpit to see the backlash against

female body hair. Though Conchita Wurst is a man performing in drag, her

performance reminds us of how uncomfortable we are with people who break gender

categories in such spectacular ways.

In the Pogonologia,

Dulaure concludes his section on bearded women with a pronouncement that no

doubt many contemporary folks would agree with:

“It is as ridiculous for a man to look like a woman, as

for a woman to look like a man.”

Perhaps the discomfort some people feel upon seeing Wurst

is that she embodies both sides of this

conundrum: she is a man who looks like

a woman, and a woman who looks like a man. Her role as an entertainer gives

her, to an extent, some liberty with her appearance. She, like the bearded

ballerina before her, is an entertainer; her gender performance is part of a

greater theatrical performance. Through her performance and her star-appeal,

however, maybe she can draw our attention to the performative nature of all

gender and the unruly body that contributes to and simultaneously undermines

this performance.