As

with many things, Columbus Day has lost much of its meaning; many of us

associate it with sales at department stores and car dealerships; some of us

get the day off while some of us don't; and all of us regularly forget we won’t get any mail today. In

a way, though, that is precisely the problem with having a federal holiday like

Columbus Day—a holiday named after a man whose contribution to world history is

dubious at best, and murderous and racist at worst.

|

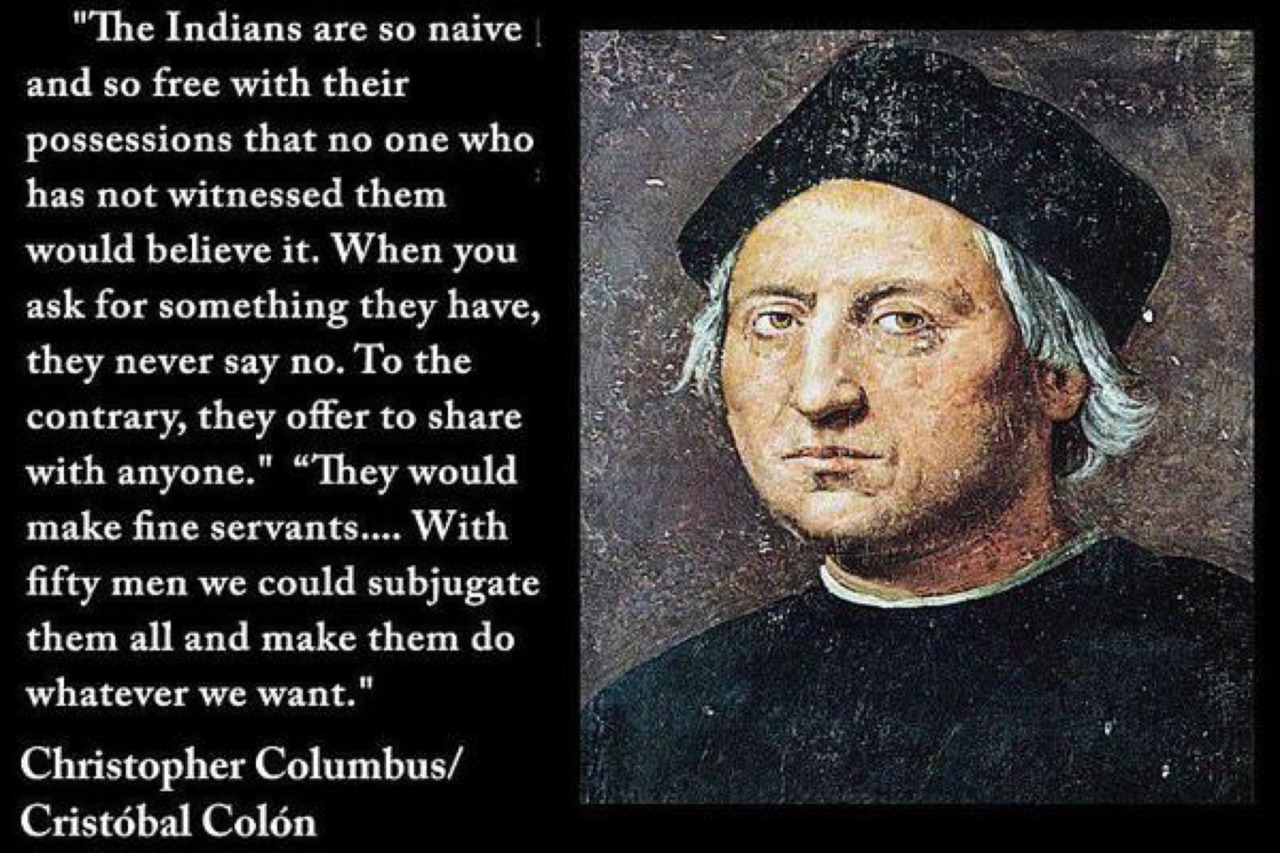

| Columbus apparently had resting bitch face; probably the only thing we have in common. |

If you bring up the idea of getting

rid of Columbus Day, or changing it, as some states have done, to Indigenous People’s Day, the reactions vary. Columbus Day was originally signed into law

after the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic organization, lobbied FDR to make it

a national holiday in order to celebrate a Catholic hero. It has become a

de facto celebration of Italian-American heritage, and attacks on Columbus Day

are interpreted by some in the Italian-American community as attacks on that

particular heritage.

None of these facts and feelings can

change, however, the fact that Christopher Columbus, aka Cristobál Colón, aka

Cristoforo Colombo, neither “discovered America” nor “proved the world was round.” His contemporaries already knew the

world was round, and he certainly wasn’t the first person to “discover” the New

World. All of this is beside the fact that he never actually sailed or stepped

foot on the continental 48 states. If anything, he “discovered” and “colonized”

(the word itself comes from the Spanish version of Columbus’s name: Colón)

modern day Bahamas, Haiti and Dominican Republic.

Then there is the more damning

evidence against Columbus that suggests he might not be such a “hero” of

history. Like many (though not all) of his European contemporaries, he believed

the native peoples of the lands he colonized were there to be seized and owned

by the Spanish crown that he worked for (he himself was Genoese/Italian!). He

writes in his letters that “I have taken possession for their Highnesses, with

proclamation and the royal standard displayed” of the land, and that the people

there “are most wondrously timorous…I gave gratuitously a thousand useful

things that I carried, in order that they may conceive affection, and

furthermore may become Christians; for they are inclined to the love and

service of their Highnesses and of all the Castilian nation.”

.jpg) |

| Columbus's "achievements" have been celebrated by artists for centuries... These images perpetuate a narrative in which Columbus is a savior and a hero for Europeans. |

In later voyages, upon realizing that the

mines of silver and gold he hoped for were not to be found, Columbus took

native peoples from the Caribbean to Spain to sell as slaves. To his chagrin as

a businessman, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain told him he could not

sell the natives as slaves. Columbus’s singular interest in the New World for

its money-making possibilities is, in a way, a precedent for later atrocities

and the dehumanization of the native peoples in the Americas. The letters of

Bartolomeo de las Casa from fifty years later discuss in great detail some of

the ways that the Spanish tortured native peoples for entertainment: burning

them alive, cutting off parts of their bodies, slicing babies in half with

swords or throwing them in the sea, etc.

|

| No caption necessary. |

Aside from being one of the earliest

practitioners and proponents of a transatlantic slave trade, Columbus was also

just a nasty guy. As governor of the Island of Hispaniola, he was tyrannical

and dictatorial; eventually he was deposed as governor and even arrested by the

Spanish crown. There are stories of how he disfigured a man arrested for

stealing corn by cutting off his ears and eyes; earlier in his voyages, a personal friend reports that Columbus

bragged about whipping and raping a native woman who did not welcome his

sexual advances.

So, should we keep a federal holiday that celebrates Columbus, specifically? Probably not. Should we recognize the far-reaching effects of his

voyages on native peoples, on our culture now, and on millions of enslaved

Africans who were brought to the New World soon after its “discovery” (re-discovery?)

by Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors? Should we take a day to deepen our

understanding of the pernicious, long-lasting effects of colonization and its

racist and eugenicist assumptions? Should we work together to forge a future in

which these issues are remembered and learned from, instead of ignored,

forgotten, or even celebrated? I think the answer to all those questions is a

resounding “yes.”