--Carl Linnaeus, Diaeta Naturalis (1733)

|

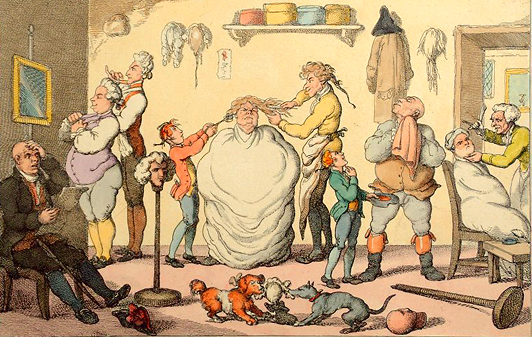

| Eighteenth-century wig and barber shop. |

Many people don't know just how many things that we take for granted as modern inventions (like dildos or condoms) actually have long historical roots. The reverse is also true: there are many bizarre historical facts and beliefs that we have forgotten or, perhaps, chosen to forget, because they became outdated (like the practices of using mouse fur to make fake eyebrows or mercury to "cure" syphilis).

|

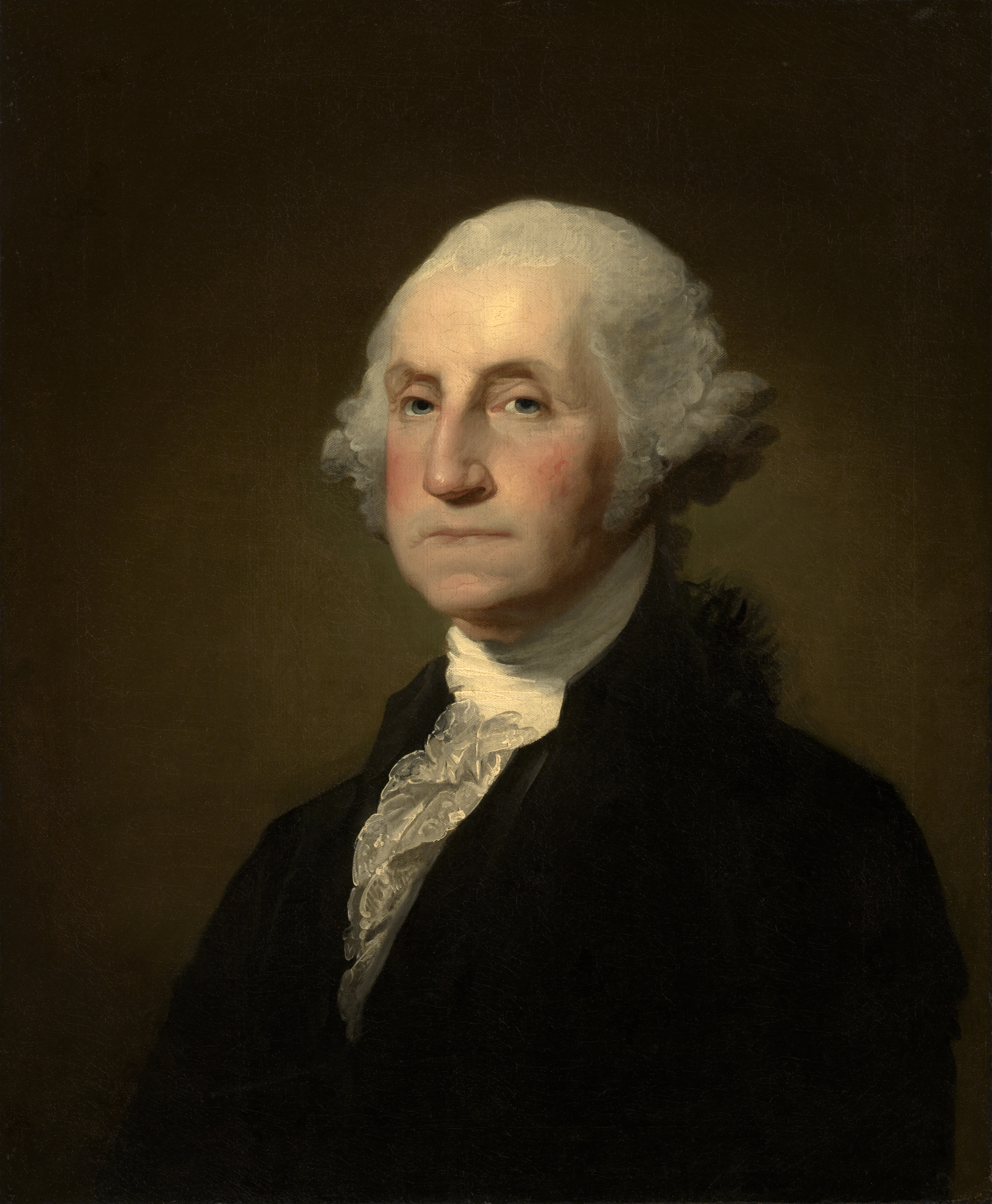

| America's famously clean-shaven founding father, George Washington. |

Some forms of facial hair, like the mustache, were almost always popular among military men, but overall, even in the military, men were expected to have a razor and keep up with shaving--or to make time to go to a barber. While the beard, as described by historian Will Fisher, was hugely popular in the Renaissance, to the point that it was a defining characteristic of mature masculinity, and mustaches and mutton chops are the calling cards of the Victorian period, the eighteenth century was almost completely facial-hair free.

The ability to grow a facial beard, however, was significant in the eighteenth-century European cultural imaginary, as it came to be thought of as an essential aspect of the white man's supremacy over other races. Eighteenth-century naturalists like Francois Bernier and Richard Bradely used the relative beardedness of different peoples to identify and classify different races. The beard-growing Europeans were "naturally" superior to the beardless Asians and native peoples of the Americas, and their practice of shaving made them superior to the "unkempt" bearded men of the African continent.

In Peter the Great's Russia, Peter himself imposed a "beard tax" on upper-class men who did not shave in hopes of moving Russia further toward the "civilized" West, further associating shaving with being evolved and Enlightened. (Though it is worth noting that both Henry VIII and Elizabeth I also levied beard taxes in England in earlier periods.)

|

| Medieval illustration of the 4 humors. |

Similarly, women who were independent, powerful, intelligent or self-sufficient were also often thought of as "bearded." Immanuel Kant, for example, invoked the beard in his attach on learned women like the classicist Madame Dacier or the physicist Emilie du Chatelet, citing that women like them "might just as well havea beard, for that expresses in a more recognizable form the profundity for which she strives." Actual bearded women, however, were dismissed as unfeminine, while the whiskers of postmenopausal women were explained through the Galenic model of reabsorbed bodily fluid--the fluids no longer expelled through menstruation reformed into facial hair.

Also of note, in eighteenth-century narratives of cross-dressing women, many women who tried to pass as men, like the female soldier Hannah Snell, had to figure out how to distract others from their lack of facial hair. Several of them compensated for this lack by soliciting the desires of other women, thus appropriating yet another kind of "beard."

No comments:

Post a Comment