|

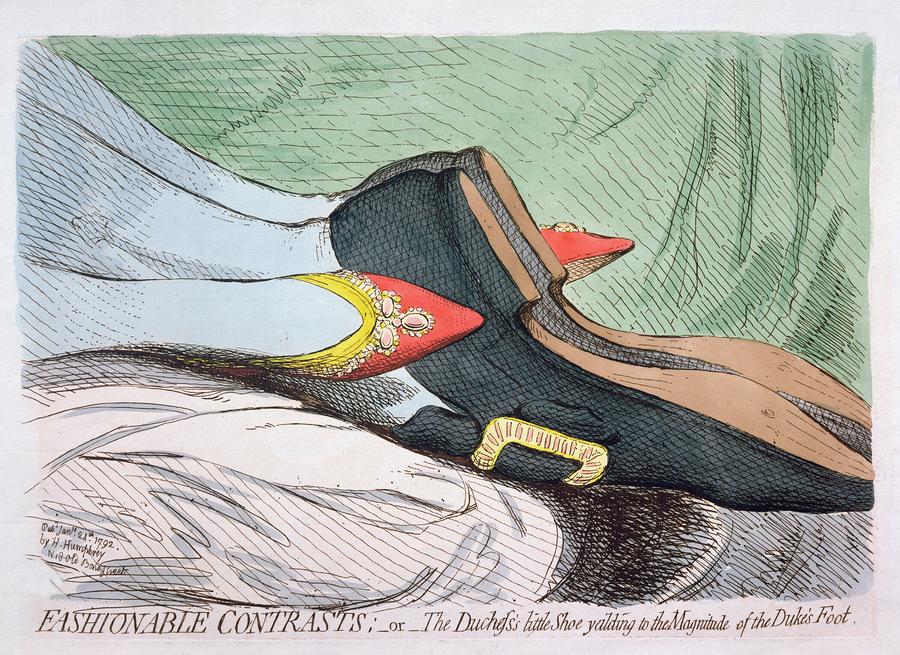

| James Gillray's "Fashionable Contrasts" explicitly channels sex through legs & feet. |

|

| Gillray's cartoon depicts ladies of questionable virtue with their legs showing from under their skirts. |

Eighteenth-century dress, as most of us know, required

women to wear long skirts, petticoats, and/or dresses to cover up as much of

their legs as possible. A “short skirt” was one that revealed a lady’s

ankle(!), and ladies who showed leg were considered titillating, inappropriate, or downright immoral. On the other hand, women who cross-dressed were often

admired for their show of a “well-turned leg.” A quote from Bernard Mandeville

describes this double-bind perfectly:

If a woman at a merrymaking

dresses in Man’s clothes, it is reckon’d a Frolick amongst Friends…Upon the

Stage it is done without Reproach, and the most Virtuous Ladies will dispense

with it in an Actress, tho’ every Body has a full view of her Legs and Thighs,

but if the same Woman, as soon as she has Petticoats on again, should show her

Leg to a Man as high as her Knee, it would be a very immodest Action, and every

body will call her impudent for it.

|

| Peg Woffington, here as "The Female Volunteer," was often admired for her luscious legs. |

In fact, what made women’s legs so titillating was

precisely the fact that they—and the crotch at the top of the legs—were hidden,

invisible and unmentionable in normal dress. According to costume historian Ann

Hollander, while men’s clothing tended to emphasize the body and “demonstrate

the existence of a trunk, neck and head with hair, of movable legs, feet and

arms, and sometimes genitals,” women’s clothes and particularly the skirt,

which “hid women from the waist down and thus permitted endless scope for the

mythology of the feminine, had become a sacred female fate and privilege,

especially after it became firmly established as a separate garment.”

The separation of the legs seemed to allude,

all too clearly, to the genitalia between them, making breeches on women an

overtly sexual spectacle. Even actresses had to contend with the condemnation

of eighteenth-century moralists on the topic of breeches parts and travesty,

while all women were aware that the showing of legs was an immoral act often

associated with prostitution.

|

| Oh Henry! Look at your bulging...calves! |

This is not to say, of course, that men’s legs were not

sexualized in one way or another, either. Eighteenth-century texts and earlier

Renaissance texts emphasize slim ankles and bulging calves as

being the definition of a graceful gam in a gentleman. Henry VIII, for example, was revered

for his muscular calves, a fact remarked on by the Venetian ambassador in 1515:

“His majesty is the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on…with an extremely

fine calf to his leg.”

The difference between men’s and women’s legs seems

mostly to be that an exposed male leg was accepted and expected in the

eighteenth century, while the appearance of a feminine leg was, in most cases,

not. Women who cross-dressed were seen as transgressors of gender codes, but,

if they were attractive enough, then their leg exposure was also acceptable.

All women who cross-dressed or even momentarily donned trousers to, for

example, ride more comfortably on horseback (like the real Queen Caroline Mathilde

who I wrote about last week!), were able to take advantage of the greater

mobility that trousers afforded.

|

| The trousers of female pirates Ann Bonny and Mary Reade in this engraving suggest a level of comfort and mobility inaccessible to women in dresses and petticoats. |

Thus, trousers were always, in a sense, a way for women

to rebel, for they signaled independence, freedom, and increased mobility. This

doesn’t mean that women in trousers weren’t sometimes co-opted by patriarchal

projects designed to recruit men to the army, to arouse men sexually, or to put

female bodies on display for consumption. Pants and legs are much more complex

signifiers in the eighteenth century than just that; the images I include here

as well as the remarks by Mandeville indicate the multifaceted, at times ambiguous

nature of the female leg, and legs more generally, in eighteenth-century English society.

|

| Isaac Cruikshank's cartoon satirizes the growing interest in ballet at the end of the 18th century and its exposure of female legs...and other bits. |

No comments:

Post a Comment