I know it’s not fair to compare 50 Shades of Grey to John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman or Pleasure; or, Fanny Hill. After all, in many

ways, they are completely different; yet, as we shall see, there are some

compelling reasons to consider them together.

50 Shades of Grey

tells the story of a young woman finishing college who is first seduced by a

sexy billionaire, only to turn the tables and become the one in charge. While

the media made much of the novel’s S&M plot twists, in the end, it is

really a novel about how the woman in the relationship, Anastasia Steele, “fixes”

her gentle brute, Christian Grey, changing his sexual tastes from BDSM to “vanilla

sex.” (That’s what the book calls it—I kid you not.) Additionally, the book

initially began as a Twilight fan fic, was written by a woman for other women, and, of course, is a product of 21st-century America.

50 Shades of Grey

tells the story of a young woman finishing college who is first seduced by a

sexy billionaire, only to turn the tables and become the one in charge. While

the media made much of the novel’s S&M plot twists, in the end, it is

really a novel about how the woman in the relationship, Anastasia Steele, “fixes”

her gentle brute, Christian Grey, changing his sexual tastes from BDSM to “vanilla

sex.” (That’s what the book calls it—I kid you not.) Additionally, the book

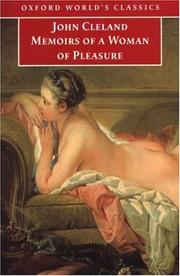

initially began as a Twilight fan fic, was written by a woman for other women, and, of course, is a product of 21st-century America. Fanny Hill, by

contrast, tells the story of a young woman who falls in with the wrong crowd

but eventually comes into her own (pun intended). Initially, she is picked up

by a madam in the hopes that her virginity will fetch the right price; while

Fanny is shocked at this idea at first, she comes around (again, pun intended)

and learns to love and enjoy sex with men (sex with women being a far inferior proposition—of course, 50 Shades of Grey

never even glances in that direction…). Fanny has many different partners over

the course of the novel, has sex for money, engages in orgies, and has no

career ambitions aside from being the loving and repentant wife of her first

sexual partner, Charles, from whom she is parted for most of the novel. The

novel was written by a man for other men, in the middle of the eighteenth

century, in England.

Fanny Hill, by

contrast, tells the story of a young woman who falls in with the wrong crowd

but eventually comes into her own (pun intended). Initially, she is picked up

by a madam in the hopes that her virginity will fetch the right price; while

Fanny is shocked at this idea at first, she comes around (again, pun intended)

and learns to love and enjoy sex with men (sex with women being a far inferior proposition—of course, 50 Shades of Grey

never even glances in that direction…). Fanny has many different partners over

the course of the novel, has sex for money, engages in orgies, and has no

career ambitions aside from being the loving and repentant wife of her first

sexual partner, Charles, from whom she is parted for most of the novel. The

novel was written by a man for other men, in the middle of the eighteenth

century, in England.

Both authors are also quite adamant that S&M is a lesser

pleasure compared to conventional sex between a male and female partner. When

asked to flagellate a man who gets off that way, Fanny acquiesces but is puzzled

by the pleasure the man gets from this act. While BDSM plays a much larger role

in 50 Shades, the novel’s protagonist

Anastasia has a similar aversion to such activities.

Lastly, both novels ultimately champion a single bond

between two (heterosexual) people who marry, in the end, and live a rather

conventional lifestyle—an interesting ending for works so committed to

titillating their audiences. In many ways, however, as a reader, I find Fanny Hill a more stimulating,

entertaining, and interesting read than 50

Shades.

Much has been written already about the many different

ways we can read Fanny Hill. Fanny

enjoys the attentions of Phoebe Ayres, even as she rejects them for not being “substantial”

enough. At the same time, she outright rejects sex between two men as immoral.

She has no problem, though, participating in orgies and watching others

participate in them. She is both a participant and a voyeur, and the

voyeuristic qualities of the novel’s heroine, as well as her evident pleasure

in recounting her past escapades (which she is meant to be confessing to an

unnamed woman….yet another literary question mark) suggest that there are many

pleasures to be found in the novel. Even though the novel ultimately resolves

Fanny’s problems through conventional means—marriage to the man she first had

sex with—there are plenty of different ways to read and interpret Cleland’s

pornotopia.

50 Shades of Grey

is not exactly simplistic, by comparison, but its single-minded focus on “fixing”

Christian Grey and Anastasia’s reluctant dabbling in his BDSM fantasies are

both grating and, frankly, not very pleasurable. The novel takes the point of

view that Christian wants to dominate his female “subs” only because he was

physically abused as a child. Such a point of view is, of course, incorrect.

Many mentally- and emotionally-healthy people engage in various types of

BDSM-play in their sexual lives, and there is nothing inherently unhealthy

about such fantasy play. Of course, the fact that Anastasia cannot “escape” her

attraction to Christian and Christian’s attraction to her is yet another

problematic aspect of the novel lifted directly from the Twilight series: the male must protect his female object of desire

through what basically amounts to stalking even though it is precisely their

relationship that puts the woman in danger in the first place.

|

| This online cartoon pokes holes in the Edward-Bella romance. |

It seems almost as if modern women’s sexual and romantic

fantasies are predicated on this trope of danger and protection 50 Shades and Twilight and heaven knows how many other romance novels propagate.

While Fanny Hill is light-years away

from being a feminist erotic novel, its heroine is able to survive because of

her quick learning abilities. Fanny learns from Phoebe and the madams how to

survive on the streets of London with nothing but her brains and her body to

see her through. Like Moll Flanders and Roxana, Fanny is able to squirrel away

money for later use. Like Pamela, an unlikely but obvious prototype for Cleland’s

heroine, Fanny finally gets what she wants—stability, money and marriage for

love—while having a whole hell of a lot more fun than Samuel Richardson’s

too-good-to-be-true protagonist.

This is not to say that the eighteenth-century didn’t

have its share of dangerous but seductive rakes—cue Richardson’s Lovelace. Or

Jane Austen’s George Wickham. The difference is that in the end, Clarissa would

rather die than be with Lovelace and Lizzy Bennet lets her dumb sister Lydia

fall for the rake. She doesn’t try to “fix”

him; she throws him over and marries the more sensible (and moneyed) option,

Mr. Darcy. Our 20th and 21st century fantasy, according

to money-makers like Pretty Woman and

50 Shades of Grey, is a Byronic hero

with money to burn who just needs a woman’s touch to be the ideal Prince

Charming. Oddly enough, though Fanny loves her Charles, he isn’t Prince

Charming—he’s hardly in the book at all. Instead, Fanny holds first place in

her story as the main actor who controls her destiny.

Am I too biased, being an eighteenth-centuryist? Perhaps.

But since there’s still another month of summer left, I suggest you read these

books and decide for yourself. After all, they are practically the definition

of summer reading.

|

| Beach reading! ...though then again, you might not want to read these books in public... |