“Be sure don’t let people’s telling you, you are pretty,

puff you up; for you did not make yourself, and so can have no praise due to

you for it. It is virtue and goodness only, that make the true beauty.”

--Samuel Richardson, Pamela;

or Virtue Rewarded

|

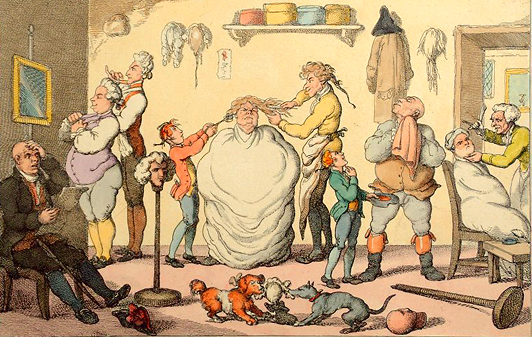

| Mr. B & Pamela |

Many of the most famous novels of the eighteenth century

recount the tumultuous story of a young woman’s first entry into society. Pamela, by Richardson, often considered

a turning point in the rise of the modern novel, is in many ways the prototype

for this type of narrative. Pamela,

and others like it, all deal with a young woman’s entry into society, her

search for a suitable mate, her development into a virtuous woman, and the many obstacles that stand in her way.Works like Eliza Haywood’s The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless,

Frances Sheridan’s The Memoirs of Miss Sidney

Biduloph (as well as its Continuation),

Frances Burney’s Evelina or Camilla, and Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda, are all variations on a theme.

A young woman without a suitable mentor or guide must navigate the treacherous

social scene (often in a “debauched” place like London or Bath) in which she is

constantly pressured to spend money, flirt freely, and associate with villains

and rakes. She is put into situations out of her control, asked to make

important life decisions, and influenced by those who want to gain by her

naivete. A single wrong decision can dog the heroine throughout life (as in Sidney Bidulph) or it can be resolved

through the help of friends and newly-discovered family connections (as in Evelina).

What these novels have in common with more recent young

adult fiction is the focus on a young teen-aged girl as the protagonist. Having

read the Hunger Games series, Ally

Condie’s Matched series, watched the

Twilight films (I couldn’t make

myself get through the books), and more recently finished Veronica Roth’s Divergent, I was struck by the recent

prominence of strong female protagonists both now and in the eighteenth

century. (How strong they are is, of course, up for debate.)

Contemporary YA fiction has broken spectacularly into

mainstream culture, starting most obviously (and pathetically) with Twilight. Twilight’s Bella is not much to write home about in terms of

agency, but the series’s love triangle, which leads Bella to follow her heart

and make some difficult decisions, has subsequently morphed into a popular

trope in recent teen dystopian fiction. The

Hunger Games’s Katniss is smarter, more interesting, and much stronger (at

least physically) than Bella; she kicks ass, takes names, and has serious

doubts about pursuing a romantic attachment during times of war—but the novel

insists on throwing her into a love triangle situation. (Jennifer Lawrence’s

rendering of Katniss has only increased her appeal, something Lionsgate

undoubtedly hopes to repeat by casting Shailene Woodley in their adaptation of

Roth’s Divergent, out in the spring.)

|

| "J-Law" as Katniss in The Hunger Games film adaptation. |

The idea of a female heroine put to various tests, thrown

into a dangerous setting, unsure of whom she can trust, asked to choose between

factions (quite literally in the Divergent

and Matched series), given a

makeover, and put in a situation where she must choose an appropriate (male)

mate is strikingly similar to the Pamela

trajectory. The stakes have not been raised, necessarily; they have merely been

updated. Running away with Wickham was social death for Pride and Prejudice’s Lydia; for many of Austen’s contemporaries,

social death was as bad if not worse than actual death. (…and in Clarissa, actually does end in death.)

It’s easy to guess why a teen-aged girl is such a titillating

choice of protagonist both then and now. She is old enough to be sexy, but

young enough to be virginal; her story is that of development but also of

romance. Richardson’s Pamela and its

various literary off-spring were meant as texts that taught young women how to

behave, think, and feel. (Though it is worth mentioning that read today, Pamela seems rather voyeuristic, as we

are asked to imagine Richardson penning various scenes in which Pamela is abused,

undressed, and groped in the dark.)

Many of the novels by female novelists like Haywood, Edgeworth

and Burney functioned not only to warn and teach young women (Edgeworth’s

father was the author of various works on female and young person’s education

and she collaborated with him on some of the projects), but also to expose and

criticize the society that gave rise to the problems these young women would

have to face. The novels function as social criticism as they illustrate the

many ways in which society works against young women, forcing them to make

difficult decisions that will affect their whole lives.

|

| A Twilight publicity image illustrating the love triangle that split female viewers into "Team Edward" and "Team Jacob" |

Today’s dystopian YA novels have an element of social

commentary, as is usual with dystopian fiction in general, but few of them

challenge social expectations of women or gender norms in any real way. The

love triangle set up by Twilight as

the “standard” for YA girls’ fiction is so lucrative, that any author with

visions of movie options would be stupid not to write one in. The romantic plot

in these works often overshadows the more transgressive dystopian elements of

the novels. The dystopian setting becomes merely a catalyst for love; the love

story becomes the focal point of the narrative, as important if not more

important than bringing down an evil government. In fact, in a series like Matched, the main character might never

have joined the rebellion against the government if it weren’t because she fell

in love with a social misfit.

On the other hand, today’s YA novels seem to encourage

qualities like self-reliance, a high threshold for pain, sacrifice for the

benefit of others, and self-confidence. Little girls around the U.S. are

begging their parents for archery lessons so they can be like Katniss.

Similarly, like many classic novels of growing up, YA dystopian fiction

emphasizes the process of “self-discovery” and understanding what it means to

be “true to oneself” and one’s core values—it’s just a shame that the biggest

part of this self-discovery is figuring out which boy you prefer.

Most of the YA fiction for young women today is written

by women; conversely, in the eighteenth century, both men and women put female

characters at the center of their stories for the explicit purposes of

educating young women (and, maybe a little, fantasizing about them, too).

Consider Defoe’s Moll Flanders and Roxana; Richardson’s Pamela and Clarissa; Henry Fielding’s Amelia;

Diderot’s The Nun; or Choderlos de

Laclos’s Dangerous Liaisons, all of

which contain female protagonists who are fascinating and complex. Now consider

some of today’s splashiest, most popular and celebrated literary male writers:

Jonathan Franzen, Michael Chabon, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, John Irving,

Stephen King…How many of them have written novels centered around the development

of a young woman? It’s a bit funny to think that of all of them, King’s Carrie comes closest to that

description. In terms of contemporary “serious” fiction, the teen girl is

negligible at best, a joke at worst.

In the end, all of these issues come back to what we, as

a society, understand teen-aged girls to be like. Both eighteenth-century and

contemporary YA novelists seem to believe that teen girls are searching for a

place to fit in, and that this fitting in is intimately tied to finding someone

to love and to be loved by in return. While not a terrible conclusion in and of

itself, it seems to indicate that our expectations of teen girls and the social

construction of teen girlhood has not changed very much in 200 years. If

anything, it seems that authors' approaches to these expectations has gotten

worse: instead of trying to correct teen girl’s stereotypical behaviors, today’s

YA novelists seem to cater to them, providing them with the kind of fantasies

that Charlotte Lennox spoofs so tenderly in The

Female Quixote.