It

is a truth universally acknowledged that the second half of Pamela is not nearly as interesting as

the first half. The first half of the novel details Pamela and Mr. B’s strange

S&M-type relationship which includes multiple attempted rapes, kidnapping,

beatings and verbal abuse of Pamela at the hands of her future husband.

It

is a truth universally acknowledged that the second half of Pamela is not nearly as interesting as

the first half. The first half of the novel details Pamela and Mr. B’s strange

S&M-type relationship which includes multiple attempted rapes, kidnapping,

beatings and verbal abuse of Pamela at the hands of her future husband.

The

second half of the novel draws out their engagement, secret wedding, meeting the

neighbors and finally reconciliation with Mr. B’s sister, Lady Davers. Lady Davers

takes a lot of convincing, as she herself is of the conviction that by marrying

Pamela, his mother's waiting-maid, Mr. B has debased himself. As they argue, Lady Davers

tries to show her brother the error of his ways by suggesting that his marriage

is the same as if she had married her groom.

“[Lady

Davers:] Where can the Difference be between a Beggar’s Son marry’d by a Lady;

or a Beggar’s Daughter made a Gentleman’s Wife?

Then

I’ll tell you, reply’d he [Mr. B]; The Difference is, a Man ennobles the Woman

he takes, be she who she will; and

adopts her into his own Rank, but it what

it will: But a Woman, tho’ ever so nobly born, debases herself by a mean

Marriage, and descends from her own Rank, to his she stoops to.”

Mr.

B’s answer perfectly sums up a sentiment shared by many people in the Western

world from the eighteenth century onward. Even now, one might argue, there are

those who would agree with his statement.

Such

a statement might have made sense in the eighteenth century, as legally, a woman

became her husband’s property upon marriage back then. In England, she automatically lost

her maiden name upon marriage, as well. For many decades, anything a woman

earned was considered her husband’s or her father’s property, and her wages

could be garnished by the man of the house and spent by him as he wished.

Thus,

an eighteenth-century author like Samuel Richardson truly would believe that it

was the man’s rank that determined his wife’s—never vice versa.

It’s

much harder, I think, to understand why so many people still believe in this

idea today. Women have joined the work force, we have entered into some of the highest spheres in the workplace, and we have made many strides towards equality.

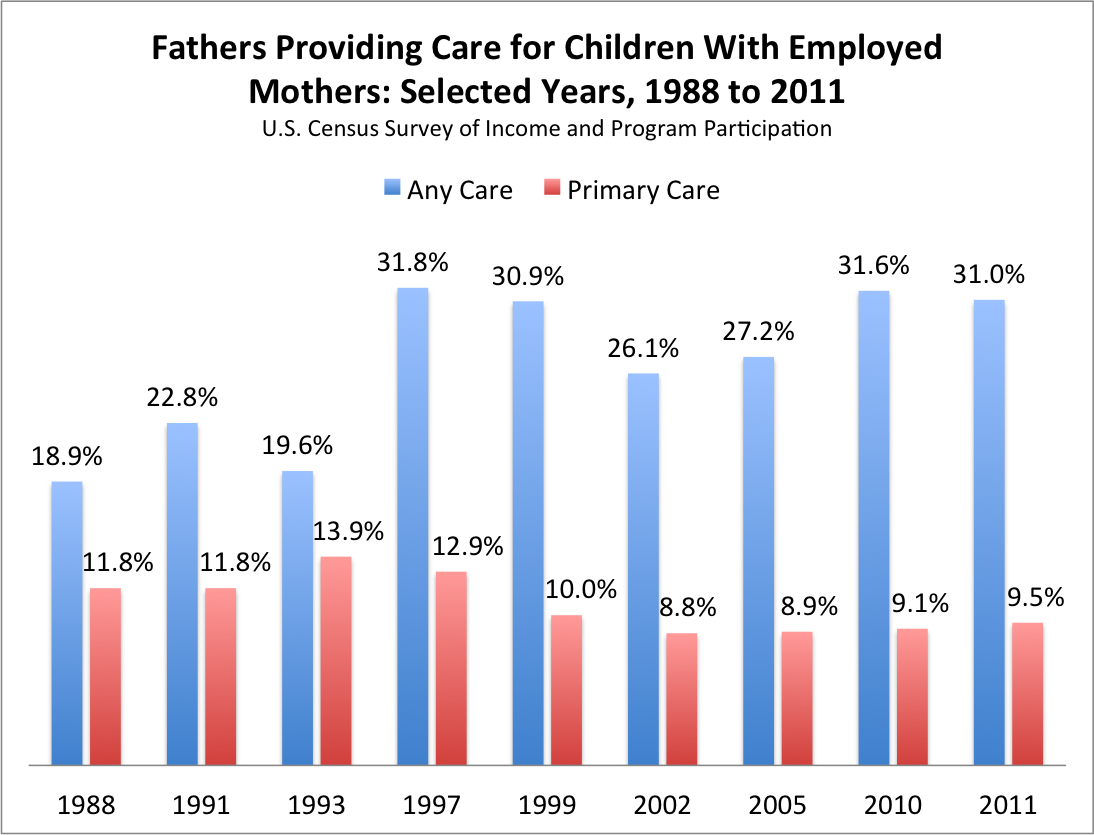

At the same time men are still the primary breadwinner in most families around the

world—and even in the Western world. Many men still have a hard time squaring

the idea that they might stay at home while their wives go to work—even as the

numbers of “stay at home dads” increase. Similarly, the lack of childcare

options in the US, coupled with the shortest amount of paid maternity leave in

the Western world mean that it still makes more “financial sense” for women to

stay home with the children while their husbands go to work. (Of course, the

lack of any kind of paternity leave for fathers only exacerbates these trends.)

|

| Even in 2011, only 9.5% of fathers are the primary care-givers for children. That's nowhere near 50%... |

On

the other hand, to go back to the eighteenth century, there were many men and

women who deplored the subordinate condition of women and who spoke out against

it. Mary Astell, Anne Finch, the women of the Bluestocking group, Jeremy

Bentham, and Mary Wollstonecraft are just some of the many writers, both male

and female, who railed against the oppression and unequal treatment of women.

Were

there any upper-class women who married far below them, in the manner of Mr. B

and Pamela? Were there any writers who challenged Richardson’s implicit sense

of righteousness that only a man could “ennoble” his wife—never vice versa? If

my readers know of any, I’d be excited to hear about it.

Class

is a slippery topic, more ephemeral, in some ways, than either gender or race.

How do we identify class? Titles, money, family name, income vs. inheritance,

position, tastes, and background all play a part. It is possible to be of a

high class but to be poor (consider the impoverished nobility of the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries). It is possible to have wealth but retain lower-class

tastes that taint one in the eyes of the upper classes (such as those who are deemed the nouveau-riche).

Pamela is considered so

revolutionary precisely because it illustrates the changing categories of class

in the eighteenth century. Pamela is allowed to be ennobled because she is so

virtuous—but also, because she is so beautiful. In the novel, beauty and virtue

are joined together, just as Mrs. Jewkes must be ugly because she has such low,

evil tastes. Later female authors, like Frances Burney and Jane Austen,

explicitly challenge the notion that beauty and virtue are always joined.

|

| We can't get enough of Jane & Rochester! |

Of

course, it’s impossible to discount the far-reaching effects Pamela has on English literature. It’s

hard to read Pamela without also

immediately thinking about Jane Eyre,

for example, and how Charlotte Bronte changes the ending so that Jane and

Rochester are more equal—by making Jane financially independent. Even Pride and Prejudice is, to an extent, a

rewriting of Pamela, where Lizzy is

rewarded with a rich husband, but not for being a servile, virtuous virgin—for being

an independent-thinking, witty young woman.

The

Cinderella-complex that persists in all of these texts—and that still persists,

even now, in popular films, television series, and best-selling novels—is perhaps

the more disturbing phenomenon. As a culture we continually insist on telling

young women that they should wish, hope, dream of having their problems solved

by marriage to a handsome, wealthy man rather than becoming wealthy and

powerful themselves…probably because wealthy, powerful women are much harder to

control.