This year, I’ve proposed a roundtable for ASECS 2015 on “Queer

Vision(s)”:

Eighteenth-century plays, novels, memoirs and even art

and poetry are often concerned with what we know and how we know it. Vision

plays a key role in defining and understanding knowledge in this period,

especially with regard to knowledge of the gender and sexuality of

eighteenth-century persons and characters. Consider the moment in which Fanny

Hill looks through the peep hole and watches two young men engaging in a

homosexual act only to fall over and faint before she can report them, or how

actresses in breeches roles were admired and desired by both men and women for

the spectacle they provided on stage. This roundtable solicits papers that will

examine the various ways in which vision is queered in the eighteenth-century

as well as how vision and the ability to see “queerly” affects who or what is

understood to be “queer.”

In the spirit of shameless plugging, I’ve decided to

dedicate a whole blog post to the topic in the hopes of promoting the

roundtable. I’m hoping to get a really great discussion going at ASECS on the

intersections of desire, perception and sexuality. These issues are, after all,

deeply tied together.

My own research on female cross-dressers led me to the

idea of “queer vision.” So often, the bodies of these women would give them away.

A flash of boob, for example, and the jig was up—or was it? In Henry Fielding’s

The Female Husband, Mary Hamilton’s

breasts are exposed at a town dance—yet she retains her male disguise.

According to Fielding’s narrator, the Doctor (Hamilton) enters into a dispute

with a man at a local dance where she has been wooing her newest conquest, Mary

Price. During the scuffle, the man “tore open her [Hamilton’s] wastecoat, and

rent her shirt, so that all her breast was discovered, which, tho’ beyond

expression beautiful in a woman, were of so different a kind from the bosom of

a man, that the married women there set up a great titter” (46-47).

How Hamilton hides her superlatively perfect breasts in

the guise of a man is left to the imagination of the reader. According to our

narrator, “it did not bring the Doctor’s sex into an absolute suspicion, yet

caused some whispers, which might have spoiled the match with a less innocent

and less enamoured virgin” (47). It seems that Mary can only see what she wants

to see; Fielding, by contrast, is coy as to what exactly he wants his readers

to see: do we see Hamilton as a villain? a rake? a misguided criminal weirdo? a

beautiful and attractive female husband?

The issue of perception and desire, however, is not

limited to issues of cross-dressing or same-sex desires. These same issues play

out in various ways on the eighteenth-century stage and in novels where

concerns about disguise, class fluidity, “passing,” and masquerade show up

again and again. For example, how could Clarissa not “see” Lovelace for what he was? Or

could see it, but still desire him despite it?

It seems, perhaps, that despite innovations in visual

technology, such as the microscope and the telescope, eighteenth-century

writers were still quite concerned with how

to see others, and how these various queer visions affect how others see us

and whom we desire. The purpose of this roundtable will be to take a look at

these issues from a variety of perspectives and through a variety of texts and

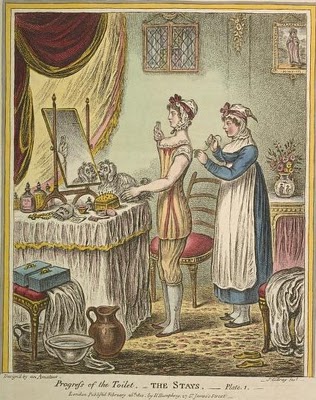

artefacts. Artists as well as writers explored the notion of vision and desire

in visual media such as paintings and cartoons. Other studies in material

culture, such as costume studies, might also make some interesting

interventions into this discussion.

For more info on submitting a proposal, go to the CFP.

Paper proposals are due by Sept. 15, 2014.

For more on boobs, see my article on Maria Edgeworth's Belinda.

No comments:

Post a Comment